Fresh Thoughts #60: The Truth About Incident Response

- Newsletter

Responding to cybersecurity incidents doesn't always get to the "truth", and that's why you must prepare beforehand.

The Truth About Incident Response

We live in a world of fact-checking and conspiracy theories.

Where truth is an absolute - and there's always one correct answer.

But this is not the world of cybersecurity and incident response.

Following cybersecurity incidents and data breaches, we get asked:

What happened?

And frequently - Was it a mistake or malicious?

The consequences of answering these questions are significant. It can mean disciplinary actions or - at worst - someone losing their job and the police investigating a crime.

While "getting to the truth of the situation" may be typical in media and society, a seasoned incident responder rarely talks about facts and truth.

They always discuss the balance of probabilities - and here's why.

The Balance of Probabilities

One of the early things you learn in incident response is hackers delete and tamper with log files. The absence of information does not mean something didn't happen. It simply means - we don't know.

A skilled responder can observe information from many sources and create a theory of what happened. Often multiple theories are developed based on what we can observe.

While business leaders may ask - "Well, which theory is true?" - that is the wrong question. It's the wrong way of looking at the problem.

A better question is - "Which theory is most coherent with the observations?".

While a better way of looking at the problem, it creates tricky situations.

Contradictory theories can be equally likely.

It depends on the viewpoint.

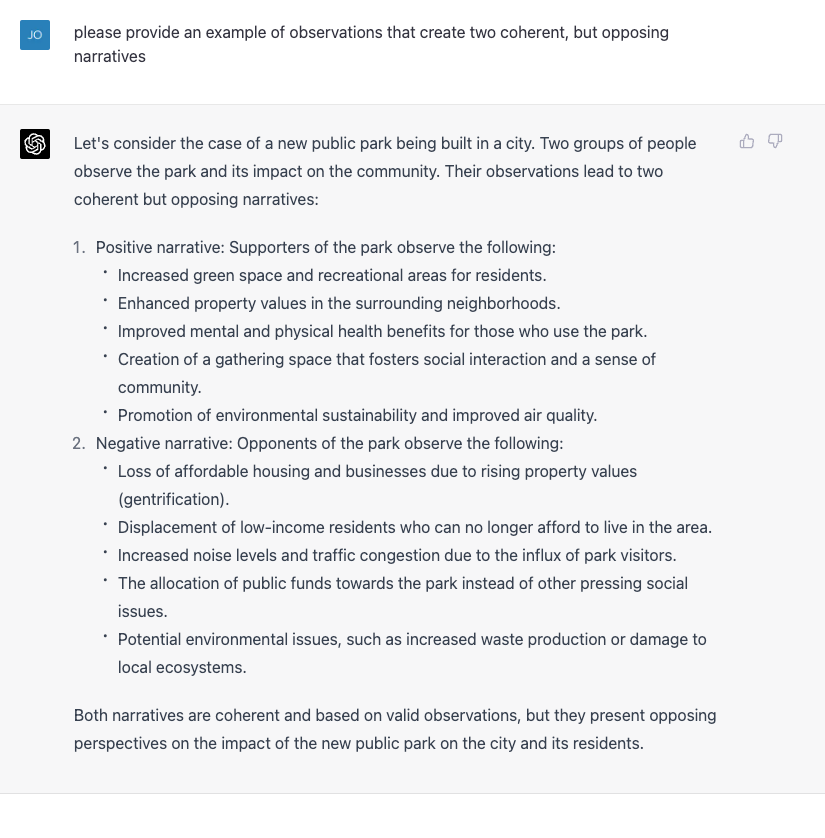

Consider the scenario that ChatGPT created - building a new public park. Both the positive and negative narratives are coherent with the observations but contradictory.

Dave Snowden - creator of the Cynefin sense-making framework - wrote about coherence and truth a few years ago. His view was:

"Better to hold multiple 'coherent' (and possibly contradictory) ideas for action at the same time. Some ideas are incoherent and are untruths. Then experiment with the ideas and see how the space changes".

In other words - you can invalidate theories and demonstrate they didn't happen, but there's no guarantee of getting to a single answer.

This situation is why you need to prepare before an incident occurs. Specifically, it is why businesses must set expectations in an Acceptable Use Policy.

Getting Rid of a Bad Apple

Consider a ransomware incident — an employee opens an attachment and enables macros. The macro installs ransomware.

What happened?

Was it a mistake or malicious?

The delivery and opening of the email can be observed, but the intent and mindset cannot.

But the observations may also include the staff member:

- Missing security awareness training - when asked.

- Regularly failed phishing tests - and avoiding refresher training.

Is it coherent to say the incident was a mistake? Yes

Is it coherent to say their intentions were malicious? No - there are many reasons for missing the training

Is it coherent to say their past behaviour shows a pattern of recklessness? Yes

Is that sufficient to pass a threshold of unacceptable behaviour? That's a judgement call...

Unless you have previously outlined what is and is not acceptable behaviour - you will be unable to enforce that judgement.